William Hayward

Written by HAHS Staff | Download a PDF of this article

One of the most frequently asked questions about the City of Hayward is where the name comes from. Was the city named after a person? The answer is yes, in a way. Let us explain.

William Dutton Hayward was born in 1815 in Hopkington, Massachusetts, a small town southeast of Boston. He lived on his father’s farm until adulthood when he moved to Georgetown to work in a shoe factory. He married Lois Bartlett in 1838. Lois died in 1840 leaving Hayward to raise a daughter, Sarah Louise.

In 1849 news of the discovery of gold in California finally reached the East Coast. The stories coming from California painted a picture of gold just laying around, easy to acquire. Like thousands of other men working away at low paying jobs, William decided to head west to seek his fortune in the gold fields. And like all those men, he thought he’d easily make his money and return home.

After making arrangements for the trip, he left Sarah Louise in the care of family members and departed on the steam ship Unicorn. The journey to California took a long six months by ship traveling along the east coast of the United States and South America before rounding Cape Horn and traveling up the Pacific Coat. He arrived in San Francisco in late 1849. After gathering supplies, he headed to the gold fields.

After many months of toiling away in the gold fields, William decided he’d had enough and started the journey back to San Francisco. How much gold lined his pockets remains unknown but it’s safe to say he did not go on to live a life of great luxury, so he most likely did not make his fortune like most gold miners experienced. On William’s trip back to San Francisco he took a route that led him into the Amador Valley through the Livermore Pass and close to the mouth of Palomares Canyon. He pitched his tent here. In a later interview, William said, “I thought if I could get a little land in this paradise, I would be satisfied.”

Take a moment to envision what that area would have looked like. Rolling lush hills and valleys, plentiful water, a temperate climate, maybe a deer and some rabbits roaming about. No highways. No houses. No fences or light posts. Maybe just a faint horse trail showing signs that someone traveled through the area. As far as he knew, the land was wide open and available for anyone to take.

But it wasn’t available. In fact, that piece of land William so admired was part of the huge ranch owned by Guillermo Castro. The story goes that two of Castro’s vaqueros came upon William and his tent and reported back to Castro that someone was squatting on his land. Now, Castro was already seeing the impact of Americans invading his land by this point. He was constantly dealing with squatters on his land. Because all those gold miners who rushed to California to make their fortune soon realized that gold was not just in the rock but in those lush, open, rolling hills and valleys that didn’t seem to belong to anyone.

When Castro and William finally connected it is unclear exactly what happened next. Some accounts say Castro offered William a job making shoes for his workers on the rancho. Other reports say Castro invited William to his home and the two hit it off. The real story remains a mystery. What we do know is that not too long after meeting, William bought land from Castro, around 40 acres near to Castro’s homestead. The home base for Castro’s operation was his hacienda located where historic City Hall is today on Mission Boulevard. Some of the acres William purchased were just a few blocks away from Castro’s home, other acres were further up the hills.

Hayward, ever the entrepreneur, pitched a tent roughly at the corner of A and Mission Boulevard and set up a general store and saloon. He had noticed all those one-time gold miners in the area and that they often traveled through Castro’s land north to south along the old mission road. By 1852 he started work on a permanent structure for a hotel. The stagecoach service from Oakland to San Jose would stop at the hotel to change horses. The passengers would disembark to stretch their legs and grab a drink or two or a meal at the tavern. Hayward’s little enterprise grew and expanded as more and more people began settling in the area. Eventually, Castro was forced to divest of all his property and move out of the country while Hayward’s Hotel put the small community on the map.

As a part of his hotel operation, William Hayward petitioned the US Postal Service to establish a post office in his hotel lobby to service the local area. On January 6, 1860 the post office was established as Haywood, California. There are two theories about this name difference. One is that Mr. Hayward’s handwriting was so bad that there was a clerical error made when the application was processed. The other, and more plausible story is that the US Postal Service had a rule about naming post offices after living persons. Since Hayward was very much alive, it was decided to call it Haywood instead. Mr. Hayward was named the first postmaster and remained in the position until 1889.

William worked closely with Castro, Faxton Atherton, and C.T. Ward, the latter two having purchased the remains of Castro original rancho before he left the country, to develop plans for the Town of Hayward. He would often use his own funds to achieve the goal of developing some of the first roads in the area.

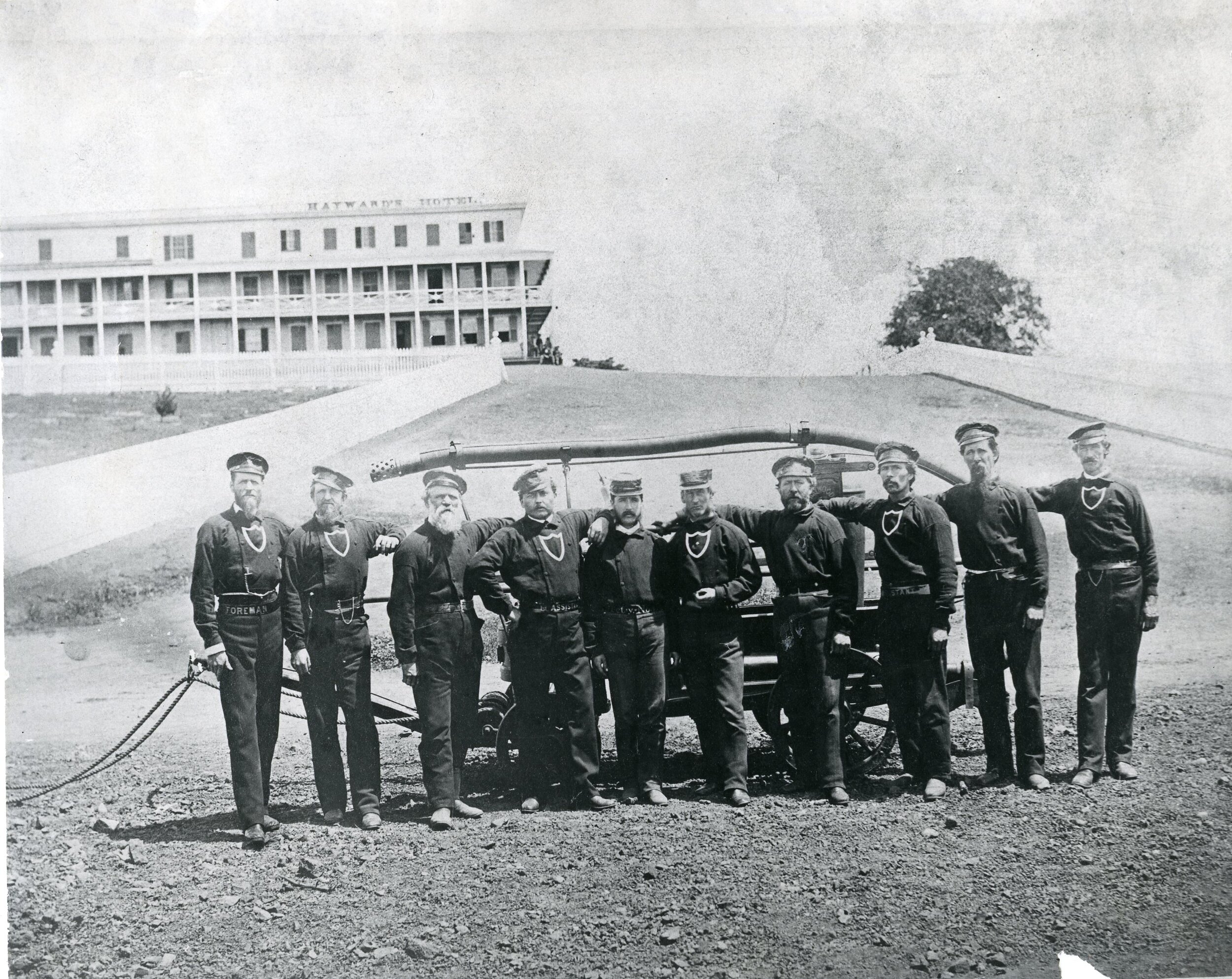

Hayward Volunteer Fire Department, c. 1876. William Hayward is the third man from the left.

In fact, William was involved in almost every aspect of the early days of the town. He served as the first Roadmaster for Eden Township and as a County Supervisor in 1856 and 1869. After the disbanding of the Hayward Home Guard, a volunteer military unit established during the Civil War, he served on a committee to use leftover funds to purchase land for a cemetery. This would become Lone Tree Cemetery. Hayward served as an original cemetery trustee from 1873 – 1891.

Over the decades he expanded and remodeled Hayward’s Hotel and farmed on some of the land he owned. In his personal life, William married Rachel Rhodes Bedford, a widow with a daughter, after a short courtship in 1866. At that time, Hayward’s daughter came from Massachusetts to live with them. In 1867, William and Rachel had a son, their only child, William M. Hayward, known as “Willie.” After their marriage, Rachel played a major role in the operations of the hotel and helped establish it as a great place to stay with good food and a warm atmosphere. Her assistance at the hotel allowed William to give his attention to all the other activities he contributed to in making the community grow and prosper.

Hayward died on July 9, 1891 as a result of skin cancer at Hayward’s Hotel. His illness had been a long and painful ordeal and he was treated regularly with morphine to manage the pain. He was 76 years old. His funeral was held at the Congregational Church (now Eden United Church of Christ). The International Order of Odd Fellows and the Hayward Volunteer Fire Department, both organizations that he had helped found, were integral in the service. The procession from the church up Cemetery Road (now D Street) to Lone Tree Cemetery was 2 miles long. All businesses were closed that afternoon and flags flew at half-mast in his honor. He was buried in a grave that overlooked the town that he helped build.

When the town was incorporated by the State Legislature in 1876, it was incorporated as “Haywards.” The “s” on the end circumvented the naming a town after a living person problem. The “s” was gradually dropped beginning in the 1890s, after Hayward’s death. William’s son, Willie died suddenly in 1893 and his daughter, Sarah Louise, died in 1909. Neither of William’s children married or had children of their own so there are no direct descendants of William Hayward. His legacy is in the city he helped found.

At his eulogy, Rev. Dr. MacKenzie summoned up William Hayward with the following words:

“Our friend was not only the founder of our town, but one of the pioneers of this state. We not only feel an interest in him today, but a hundred years hence there will be a greater interest in knowing just the spot where he pitched his tent and how he spelled his name. His name is historic, his life is historic, they belong to the history of this State.”

This article originally appeared in the Tri-City Voice.