The World War II Home Front in the Hayward Area

Written by HAHS Staff | Download a PDF of this article

Introduction

When Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 7, 1941, it immediately changed how Hayward area residents lived their everyday lives for the following 4 years. Hundreds of local men served in the armed forces during the war and many were killed in action in Europe and Pacific. Some local women also volunteered for service as “Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service”, better known as WAVES. Like the rest of the country, Hayward area residents served bravely, both at home and abroad.

On the home front, wartime rationing and restrictions had major consequences for residents. Some were positive. Residents donated rubber and metal toward local scrap drives and gave blood to the Red Cross. Other consequences were decidedly negative, especially the incarceration of Japanese Americans for no other reason except their race. This essay explores some of the ways the Hayward area was impacted by World War II.

The USO: “Hayward Hospitality House” During WWII

Hayward Veteran's Building, known during the war as the “Hayward Hospitality House” (HAHS Collection)

Hayward’s branch of the United Service Organizations (the USO) started in March 1942. Milt Dohner, a local businessman, agreed to head the new branch and begin a fundraising campaign. The first fundraising goal was set at $5,000. What exactly that money would be spent on was unclear, but like most other groups in early 1942, there was a push to raise money in support of the war effort.

Within a month, Hayward’s USO had raised $1,700, most of that money coming from John Haar’s Pickle Works and its employees. Soon after, fundraising began to fall flat and the USO put out a call to local women to help raise more funds. For the rest of 1942, there is little mention of the USO or Milt Dohner. At that point there was still no location for the USO.

In 1943, a year after the USO organized in Hayward, the Hayward Lions Club renewed the effort to acquire a space for the USO to function and hold events. The renewal of interest was due in part to the fact that Camp Parks, a new US Navy base, just over the hill in Dublin, was growing quickly as well as Hayward’s Army Air Field (today’s Hayward Airport).

A week later, on March 17, 1943, it was announced that the Veteran’s Hall on Main Street would be used as the “Hayward Hospitality House”, operated by the Hayward USO. The move was backed by veteran’s organizations and had a budget of $11,000 dollars to begin operations. A few months later the city allocated $600 a month to operate the hall consistently. Later that fall, Hayward’s mayor Don Leidig took over Milt Dohner’s position as head of the Hayward USO. Leidig would lead the operation through the conclusion of the war.

Throughout 1943 and 1944, the Hayward Hospitality House held weekly events for servicemen. Periodically, the USO held open houses to allow the public to see and participate. The open houses were well advertised events with lots of publicized music and dance acts, including hula dancers, radio DJ’s and various dance and comedy tropes. The most consistent, with appearances at least once a week, was the Camp Parks Band. Local acts like the “Valdez Show” were also featured often. Seasonal Halloween, Thanksgiving and Christmas events also took place in 1943 and 1944.

The USO provided a place for servicemen, most of whom were far away from home, a break from the war. It gave them a chance to relax a bit, dance or talk with a pretty girl, grab a cup of coffee and a snack, maybe even take a quiet moment to write a letter home on the stationary provided. It was a moment of normalcy in a chaotic time.

"Camp Parks Band" at the USO (HAHS Collection)

Other more serious anniversaries and events, such as Pearl Harbor Day, were commemorated at the USO as well. The USO was operated by volunteers, mostly women. A December 1943 editorial praised area women for their work. By the end of 1943, less than a year after opening, the USO was entertaining as many as 12,000 people a month. By the end of the war, over 200 volunteers were credited with donating time to the USO. The flow of servicemen, mostly from Camp Parks and the Hayward Army Airfield, increased more as the war went on. At the start of 1944, signs were placed around town to guide service men to the USO.

The high point for the Hayward USO came in November 1944. An event hosted by the Lions Club drew 1,300 servicemen. The event set the record for the largest one-night crowd since the acquisition of the Veteran’s Hall for the Hayward Hospitality House. At the end of that same month, the USO presented pins to volunteers, commemorating those who had given at least 50 hours of service to the USO.

In March 1945, the Hayward USO celebrated its second birthday—only a few months later the war would end. In September 1945, less than a month after Japan’s surrender, it was announced that the Hayward Hospitality House would be closed and the Veteran’s Hall returned to the Veterans starting in September. The closure was deemed necessary so that Veterans’ groups could accommodate the influx of returning servicemen.

In October, the USO conducted one last large program to commemorate its 30 months in existence. The program featured a huge volunteer recognition party. Hundreds of volunteers were recognized for donating time to the USO in its almost three-year existence. The Hayward Journal summarized the accomplishments of the USO in Hayward: 30 months of service, half a million servicemen hosted, hundreds of volunteers, and a total of 270,000 hours of their time donated to the Hayward Hospitality House were tallied up at the closure of the USO branch. With that, a brief chapter in Hayward’s wartime history concluded.

Blackouts, “Dim-outs” and Air Wardens: Civil Defense and Community Response during WWII

Civil Defense activities in the Hayward area during World War II consisted primarily of blackout and “dim out” drills, as well as volunteer aerial observation in a network of observation towers.

The civil defense activities in Hayward were part of the larger “Civil Defense Corps”. The corps was created by President Roosevelt and dissolved in 1945 by President Truman. During the war, the Civil Defense Corps encompassed the training and recruitment of community volunteers to become auxiliary police, firefighters, medical responders and “decontamination squads”. The World War II Civil Defense Corps is separate from the civil defense bureaucracy of the Cold War era. That body was not created until 1949.

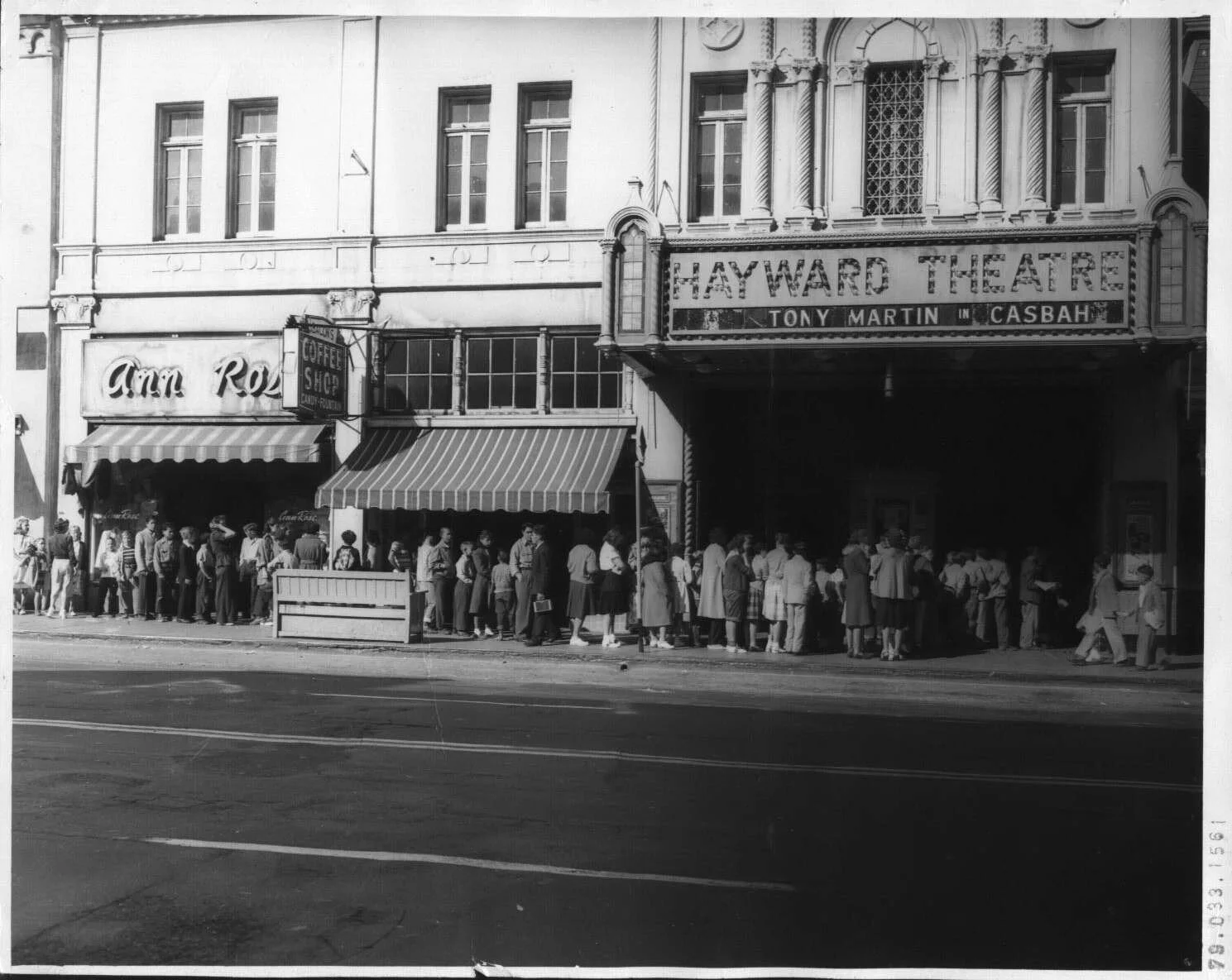

The threat of aerial attack by the Japanese led to the establishment of blackout districts up to two hundred miles inland from the coastlines of the United States. The “Blackout Corps” in Eden and Washington Townships had a total of 1200 volunteers to help enforce the regulations. Initially there were eighteen “blackout districts” in Hayward, twelve in Castro Valley, fourteen in Ashland and two in San Lorenzo. The blackouts were straightforward and required turning off outdoor lights as well as indoor lights and the use of curtains to block viewable light. Advertisements for “dimout shades” for sale at Montgomery Ward appeared weekly in local newspapers. In downtown Hayward, neon lights were banned and the Hayward Theater marquee was kept off.

The Hayward Theater 1948. The marquee was turned off early during the war. (HAHS Collection)

As soon as the blackout drills began, small information forms began appearing in the newspaper. The forms asked readers to fill out basic information for households including the numbers of children, elderly and disabled. This was done so that in the event of an air raid, block wardens knew what type of first aid assistance was necessary for each home. Block wardens were volunteers whose job it was to enforce black out and dim out regulations as well as be a liaison between civil defense authorities and their neighbors. Above all else they were first responders to an emergency situation.

In the summer of 1942, small salmon colored cards were issued to Hayward area school children so that in the event of a major disaster, they could be quickly identified. About a week later students exchanged those cards for metal i.d. tags for identification. They were issued at Castro Valley, Palomares, Ashland, Markham, Russell, San Lorenzo, Independent, Tennyson, Sunset, Mt. Eden, and Valle Vista schools. The tags were provided free of charge by the civil defense authorities “to make possible and facilitate the identification of both children and adults, and to prevent temporary or long family separation in the event of injury or loss due to enemy action or disaster, it is necessary that all persons wear this metal identification tag at all times.” Even though the Hayward area was nestled in the East Bay, the threat of attack was taken very seriously. Identification tags were not the only materials issued either. That same summer gas masks were issued to civil defense first responders in Hayward, Castro Valley and Ashland. It was noted there were not enough gas masks for civilians.

When blackout drills were conducted, Hayward area residents were alerted by a large siren above the Hayward Firehouse. And by the end of 1942, blackout drills were being held regularly. In charge of the operation was Jack Holland. Holland was designated “Chief Air Raid Warden” for Hayward. Holland was the head of 250 block wardens who met regularly with the police department to enforce blackout and “dimout” regulations.

Drills continued to be held throughout 1942. In 1943, restrictions on lighting began to ease. Perhaps most importantly, in November 1943, dimout regulations ended in downtown Hayward. This meant neon signs and theater marquees could be turned on once again. These lights had not been used since at least early 1942. A year later, Christmas trees were again allowed outdoors, with the stipulation that someone had to be on hand to extinguish them in the case of an air raid. Even though regulations lightened, periodic blackout drills were still ordered. It was not until August 9, 1945 that California Governor Earl Warren officially ended blackout drills.

Observation Towers

The observation towers of World War II were set up to recruit civilian volunteers to scan the skies for enemy war planes. Observers were given some training in spotting and listening for Japanese aircraft. Ideally observation posts were staffed 24 hours a day. These posts were considered the first line of defense in the Hayward area and along the California coast.

A June 1942 editorial titled “Crisis! Observation Post facing Shut-Down Because of Shortage In Man Power” summarized the state of the observation posts. Hayward Mayor Don Leidig announced that three observation towers would need to be closed due to lack of volunteers. A staff of about 450 volunteers was needed to man the posts twenty-four hours a day. Any citizen over the age of 15 could volunteer for as little as two hours a week. They could serve at the four area towers including Castro Valley, Ashland, the Hayward Highlands or Russell City. Women were especially encouraged to volunteer for shifts at these observation posts.

In August of 1942, fifteen observers received special pins for 100 hours of service. Among the recipients was Hayward historian John Sandoval. By April 1943 Russell City’s observation post was also holding ceremonies for 100 hour observers with some 140 volunteers watching the skies above Russell City. After 1943, there is little information regarding the observation posts other than a few passing references. The observation towers were quickly dismantled with the Civil Defense Corps in 1945 by President Truman.

One of the ground observers, Nell Simpson, at her post in the Hayward Hills.

Agriculture and Canning

Hayward’s primary industry during World War II was cannery work. Both the California Conservation Company and Hunt’s Cannery employed men, women, and high school students. Numerous advertisements and editorials appeared in the summer of 1942 asking for women and “businessmen” to volunteer their time in the canneries to save “California’s vital crops.”

Students attending Hayward Union High School were used as laborers as well. In October 1942, Hayward Union High closed so that students could help harvest tomato crops as close as Pleasanton and as far as Contra Costa County. The high school was closed for nine days in cooperation with local farmers. At least 25 Hayward High girls camped at the Pleasanton Fairgrounds for two weeks during the harvest. All told, Hayward Union High School students were credited that year with picking an estimated 62,800 boxes of tomatoes.

For the 1944 season, Hayward students were asked to join other residents in the cannery, not the fields. In August 1944, the Hayward Union High School board of trustees pushed back the start of the school year by two weeks to keep over 250 students employed at the cannery longer. The plea for the delayed opening came directly from the California Conservation Company and Hunt’s canneries. That same month, advertisements for 250 men and 750 women for cannery work began appearing. The ads were paid for by the Hayward “mayor’s committee for cannery requirement”. More editorials pop up in support of the canneries at this time. Unlike in 1942, canneries are viewed as essential defense work by 1944. The next summer, in 1945, the advertisements and pleas for women and men to work the canneries appeared again. Even after the war was over, there were still pleas from the canneries for workers to stay on the job. Canneries and agriculture would remain important in the aftermath of World War II.

Scrap Drives

In addition to the seven nationwide war bond drives, there were locally organized scrap drives. Scrap drives were organized events that local officials held to collect materials for the war effort. The collection of metal and rubber were especially important during the first few years of the war.

In June 1942, Hayward held its first large-scale “Rubber Drive”. Hayward residents, led by the Lion’s Club, collected 496,296 pounds of rubber. Boy Scouts went door to door asking people to gather what scraps they had. Less than a month later, another Hayward area drive collected 742,696 pounds of rubber.

Also that summer, Mt. Eden residents managed to collect fifteen tons of scrap metal in only one day. A larger scrap metal drive in Hayward collected a staggering 328.5 tons of metal. The items collected included bicycles, bed springs, and Model T Fords. Rumor has it, even prohibition era alcohol stills were “donated” to the cause. According to the Journal, that particular scrap metal drive set a statewide record. These scrap drives made 1942 a successful year for Hayward’s contribution to the war effort.

Subsequent scrap drives did not match the amounts collected in 1942. Other area communities held smaller drives sporadically, but excitement seemed to plateau. Unlike 1942, later scrap drives did not feature large full-page advertisements in local newspapers taken out by the city. Instead, later drives were pushed by local chapters of civic clubs. The final scrap metal drive in Hayward happened in March 1945. The drive was spearheaded by the Business Women’s Association. The event took in four and half tons of scrap. Unlike earlier drives, the news about it appeared in a small article on page four.

The Red Cross

Red Cross volunteers in Hayward, 1951. The Red Cross operated continuously in Hayward during World War II. (HAHS Collection)

The Red Cross opened a wartime office in Hayward on January 1, 1942. It was located inside of City Hall (on Mission Boulevard). Like the air raid wardens, fire and police services, the Red Cross was considered a part of the civil defense structures that were formalized by early 1942.

The Red Cross not only operated in Hayward, but smaller communities had their own branches. In fall of 1942, a Red Cross service center opened in Mt. Eden, joining another branch at the Castro Valley Grammar School.

The Red Cross ended 1942 successfully with a 100-person blood drive. Part of what made these drives successful was the Red Cross’ mobile blood bank. The mobile unit was essentially a truck that arrived at various locations in the Hayward area on a monthly basis to collect blood. In this instance, the mobile unit was set up at a Presbyterian Church. The mobile unit continued to arrive in town, and the office located in city hall made sure donors were signed up to meet monthly quotas.

The Hayward Red Cross office continued operation quietly in the background for the duration of the war. Blood donation itself reached a high point in the area in late 1944, when the mobile unit had 177 donors in a single day, more than exceeding Hayward’s donation quota. As a civil defense organization, the Red Cross played a quieter, but important role in Hayward.

To read about Japanese American imprisonment during World War II, please click here.